How to Design Beyond the ADA

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

The Americans with Disabilities Act is now over 30 years old. Is it enough to guarantee disabled people’s rights to access public space?

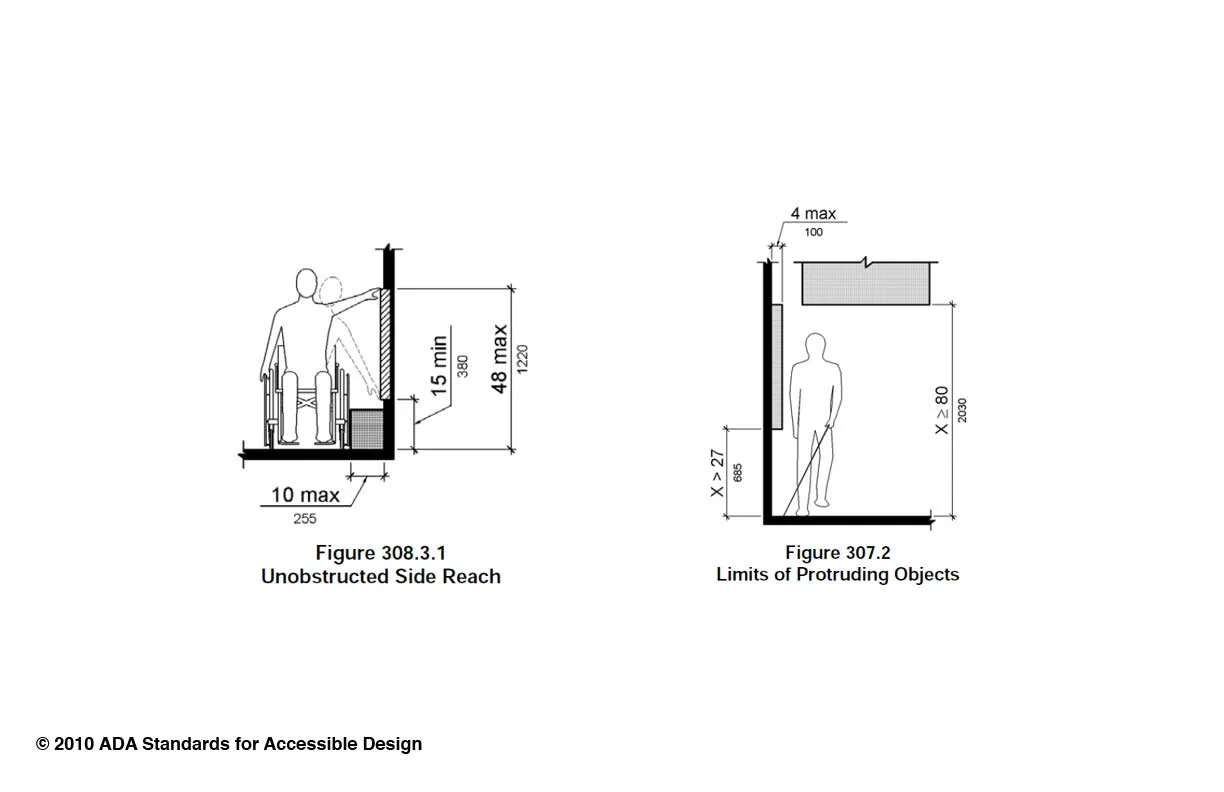

Image Description: Two black and white graphics with minimal shading from the ADA Standards for Accessible Design (2010) side by side. The left is Figure 308.3.1: Unobstructed Side Reach, with a person in a wheelchair illustrating a 15’ min height off the ground and 48” max height for unobstructed side reach. The right is Figure 307.2: Limits of Protruding Objects, which illustrates a Blind person using a tactile cane and a 4” max protrusion.

It has been over 30 years since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), in 1990, yet the disabled community is still fighting for access to public space; and the battle is far from over.

Access to public space is a civil right, not a privilege, yet disabled people’s rights to access and enjoy public space are still being questioned and challenged. As landscape architects, designers, and related practitioners, we often rely on the ADA Standards for Accessible Design as a catchall to lead our efforts in creating accessibility. This set of standards was first released a year after the passage of the ADA, and its most recent version was released over 10 years ago, in 2010.

The ADA Standards are a huge piece of legislation for the disabled community in the U.S., helping the disabled community to enforce rights to access public space and the very right to be included in design. However, the ADA Standards are not perfect, nor do they solve inaccessibility issues for the entire disabled community: the standards focus mostly, yet in a very limited capacity, on the needs of wheelchair users and Blind / low vision folks, and there is little to no mention of other disabilities (such as: Deaf and hard of hearing people, neurodivergent and psychologically disabled people, or other intersectional disabilities). They focus heavily on architectural interiors rather than broader, public spaces, and are assumed to cover the basic needs of every disabled person. This is not the case.

Today, we are limited in how we think about accessibility, as designers. We grumble about the ADA Standards and any further guidance on it. We cite costs as the largest “roadblocks” to applying accessible and inclusive practices; but, in reality, the costs are much higher when we are sued later for non-compliance to the ADA and other safety codes. We enter projects treating the ADA Standards like a limitation, as a law we must follow and as an ugly blight on our designs. So it truly comes as no surprise that we begrudgingly apply the standards as an afterthought, with little to no creative input.

We need to stop thinking about access so negatively. We need to rethink our methods for creating a more inclusive and accessible public realm by building upon the ADA Standards as a foundation, through direct input from disabled stakeholders and experts. In other words, yes, I’m saying the ADA Standards are - and should be treated as - the absolute bare minimum in each of our projects.

I believe Universal Design has the potential to change the way we view access to the public realm, far beyond the ADA.

The seven principles were created in 1997 by Ronald Mace, a disabled architect, consultant, and professor at North Carolina State University. They are very open-ended principles that are not legally binding; we find Universal Design principles in many resources. Surprisingly, Universal Design is not treated as common sense today, and I believe this is due to the fact that we continuously equate our ideas of access and inclusion with the ADA Standards, which we grumble about and dislike. Universal Design can actually be used as a powerful, creative tool to drive our designs beyond the bare minimums of the ADA Standards. Due to their very flexibility, they create a large bandwidth in which to apply beautiful and accessible design elements that can be customized and catered to disabled stakeholders’ needs, as well as our design’s intent.

However, Universal Design is still not a one-size-fits-all approach, and that’s not what I’m aiming for here (and neither should you). This should not be the goal because it’s virtually impossible to design with every single person’s needs in mind, but we can definitely meet more people’s needs than we currently are, today, by challenging our assumptions about access. We need to critique all standards and principles given to us, unlearn them and grow them, and couple them with direct feedback from the disabled community, particularly those local to the project at hand. Only then can we design immersive, adaptive, and accessible designs, where disabled people can thrive and experience joy. This is a radical process and a conscious choice that can be made by each and everyone one of us as designers.

equitable use

flexibility in use

simple & intuitive use

perceptible information

tolerance for error

low physical effort

size & space for approach & use

Universal Design Principles, NC State University, The Center for Universal Design, 1997

Method

I believe we can start the process of designing with disabled people by treating the ADA Standards as the bare minimum, the foundation from which to build upon. The next step is to creatively input Universal Design principles, as an adaptive tool. And the final step is to bring in disabled stakeholders and experts through the design process, as a qualitative control, which goes beyond our typical QAQC. Trial and error are completely necessary to achieve the best results.

Image Description: A diagram for designing with disabled people, a series of four black circles with white text within. Each has a bright pink magenta dashed bracket above and a text label. The left circle reads: ADA Standards for Accessible Design. Above it is the pink dashed bracket, and is labeled: law. Below the circle is a bright pink arrow pointing upwards to the circle, and text below it reads: quantitative bare minimum. The second circle reads: Universal Design Principles. Above it is the pink dashed bracket, and is labeled: creative tool. The third circle reads: disabled stakeholder feedback, and the fourth circle reads: disabled expert feedback. These two circles share a pink dashed bracket, and it is labeled: participation. Below these two circles is a bright pink arrow pointing upwards to the space between the two circles, and text below it reads: qualitative control.

Example

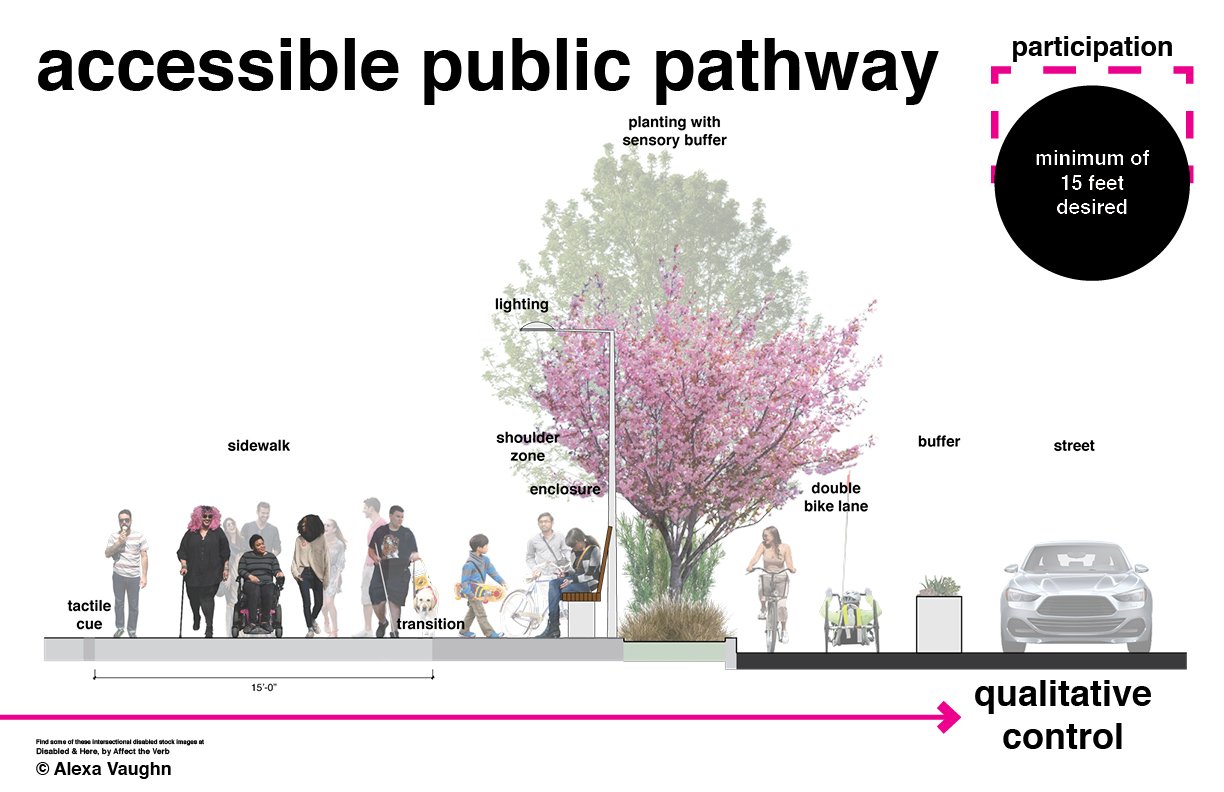

For this scenario, I’ve created an example of an accessible public pathway. We assume the path is graded at a proper accessible slope (less than 5% running slope, and less than 2% cross slope). We will focus on width, space, and amenities on the path - elements that make it both accessible by bare minimum as well as beautiful and joyful at maximum achievement.

Image description: The same diagram as above, this time with the example of an accessible public pathway. In the first circle, the text now reads: Section 403.5.1: Clear Width [36”]. The second circle reads: 7. Size & space for approach & use. The third circle reads: minimum of 10 feet needed. The fourth circle reads: minimum of 15 feet desired. Brackets and arrow text remain the same as the previous slide.

1. We might begin by taking Section 403.5.1 of the ADA Standards, which requires a clear width on accessible routes, at a minimum of 36” (or 3 feet). There is nothing exciting and only one wheelchair user can fit comfortably. The original ADA standard graphic shows a plan view, and it is very tight. It would be very uncomfortable to communicate and move through this space with more than one person.

2. In the next step, we can take a look at the seventh Universal Design principle, which requires size and space for approach and use. Universal Design principles are broad and ambiguous, so we can begin to think about what this means, with materials, placement of design elements, and usability beyond that basic standard. For example here, I’ve applied 10 feet of width to this sidewalk, which happens to be a DeafScape principle. There are tactile cues at either side, to delineate transition off of the sidewalk. There is room for seating, lighting, and planting well off of the pathway, which limits obstructions. And then we have a bike lane and room for cars.

3. Furthermore, we can take another step by incorporating additional feedback directly from a diversity of disabled community members who might just prefer even more space than 10 feet on this particular street, for more comfort and enjoyment of that space. And so we can adjust our assumption for 10 feet, which went up from the bare minimum of 3 feet, up further to 15 feet, and provide more amenities like enclosures and sensory buffers to account for overlooked needs and preferences. In this instance, there is more room for everything and everyone using this sidewalk because we’ve prioritized disabled people’s needs and we’ve met far more than the bare minimum requirements of the ADA. Because we have achieved access (our primary goal) and gone beyond those bare minimums, we have also created a better and more beautiful pedestrian-oriented accessible public pathway.

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

Disclaimer: This is not meant to serve as legal advice, nor serve as a substitute for access laws or requirements. These opinions are my own, as a disabled / Deaf person, and not necessarily those of my employer. Please consult the ADA Standards and other applicable state and federal codes for legal accessibility requirements for each project you pursue. This is meant to serve as a creative tool to be used as a supplement to any / all legal requirements, which must be met as bare minimum, before branching out to Universal Design principles and direct disabled stakeholder and expert feedback.